The Dangers of Doing Good

"To do evil a human being must first of all believe that what he's doing is good." Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

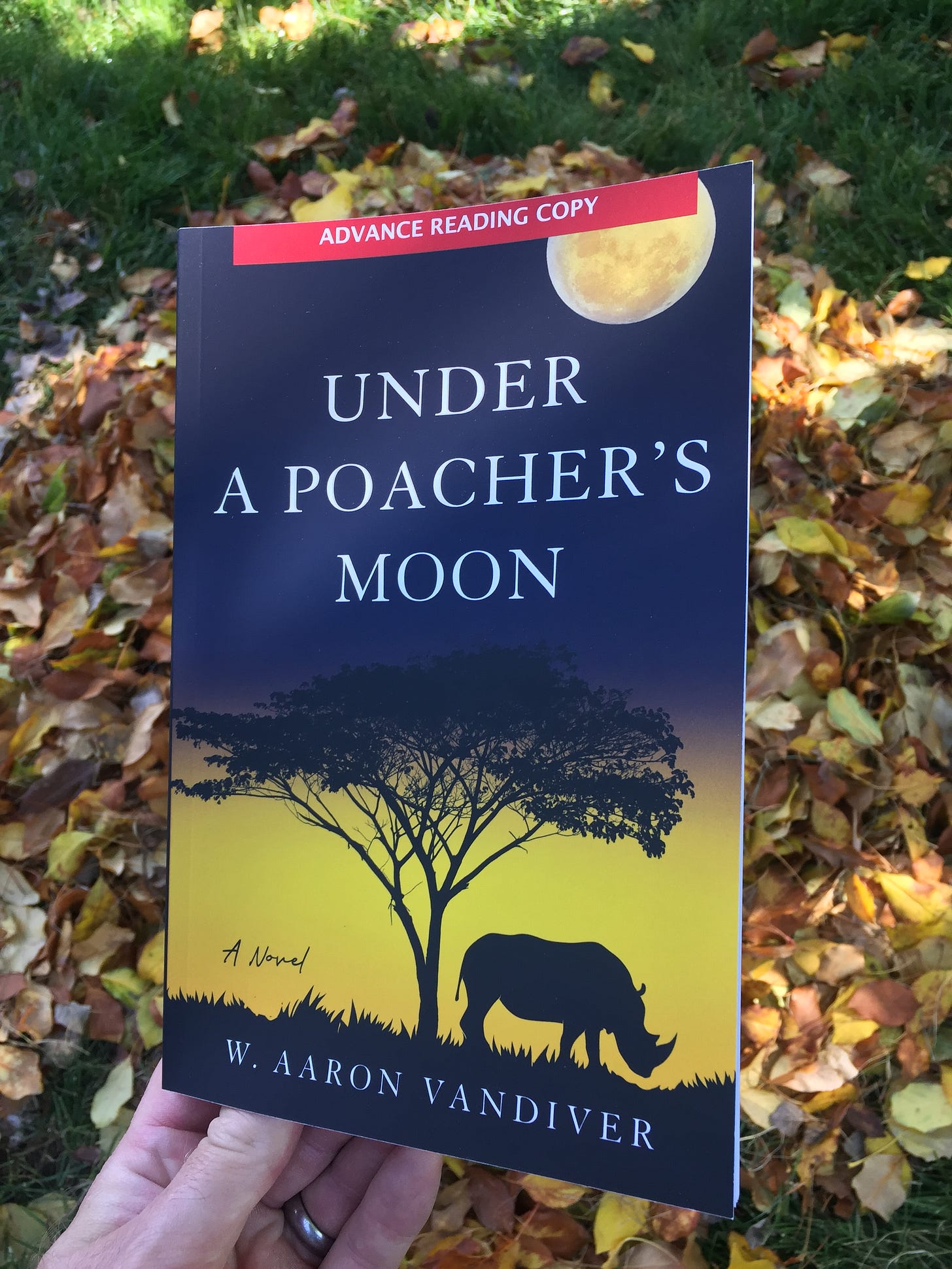

Book Update

Advanced Review Copies (ARCs) of my book are now available in electronic or hard copy format. If anyone wants to read an ARC and submit a review please send me an email.

Editorial reviews of the book will start rolling in at the end of this month.

I am putting together a “Street Team” of readers who on the day of release (Feb. 1) will (1) search for the book on Amazon (this helps the algorithm find and promote the book), (2) write an Amazon review after making a verified purchase, and (3) then share the book on social media. If you are interested in helping in this way, please email me.

I am trying to send out this newsletter on the 1st and 15th of each month with book updates and original content such as the essay below: The Dangers of Doing Good.

One of the challenges to writing these days is that everyone is focused on one particular topic (I’m sure you can guess which one), which is very difficult to write about in an evenhanded way. In these essays I will attempt to rise to that challenge and tie in current events with the themes of my book.

The Dangers of Doing Good

A number of years ago when I started writing my novel about rhino poaching I was full of righteous fervor. In my book the lead female character, an American named Anna, becomes obsessed with trying to stop the slaughter of the African wildlife she has fallen in love with. This obsession is quite understandable. Her character grew out of my own feelings as I first got involved in conservation. To some extent the book began as an effort to come to terms with the “sixth mass extinction” rampaging across the globe, including the possible extinction of the world’s most iconic animals like rhinos and elephants. I remember when I first learned that the Earth has lost over 70% of its wildlife in the last 50 years. It’s an overwhelming number. How do you deal with something so huge? What do you do when confronted with life on the planet being wiped out at such a scale? The frantic, urgent feeling that something “must be done” is something you feel very intensely when you first open your eyes to this problem. In many ways this is a healthy feeling that can stimulate positive action.

Over time, however, I came to see how fervor for any cause, no matter how good, can lead people to take overzealous or even reckless actions that dehumanize and destroy other people, and may even make the underlying problem worse. Much of the book’s drama comes from the tension between the righteous urge to do something “good,” and the real-world effects, including the unintended consequences, that can ensue when one risks becoming too fanatical in the pursuit of a Good Cause.

The lead male character in my book, Chris, gives Anna the following warning about the dangers of zealotry before they embark on a chase of the poachers:

Africa is full of do-gooders, many of them making things worse. Now why is that? Why do well-meaning people from all over the world come to Africa just to fuck things up? Dissertations could be written on the subject, and probably have been. My take is the world is a complex place, and Africa even more so. It isn’t interested in shaping itself to your preconceptions. It is bigger and wilder and more complex than we can ever grasp. We try to hold on and it slips right through our fingers like sand.

The difficulty of trying to shape a messy world to our preconceptions of goodness and justice is a lesson Anna learns in immediate and visceral ways as the story unfolds.

The travel writer Paul Theroux, who has documented his travels all over Africa and much of the world’s far-flung places in books like Dark Star Safari, has always liked to lampoon the legions of “do gooders” from the West, the distant outsiders who try to “fix” Africa and other “underdeveloped” areas. “Oafs driving Range Rovers and staying in 300 dollar a night hotels,” he calls them, idealists mixed in with profiteers who are always trying to impose top-down solutions in places they barely understand. (He had this to say a few years back about the U2 singer, Bono: “There are probably more annoying things than being hectored about African development by a wealthy Irish rock star in a cowboy hat, but I can’t think of one at the moment.”) While the desire to help may be heartfelt, it can be misguided. It can turn into a cover for greed and selfishness and corruption, and end up causing more harm than good.

“Good Causes”

“If you see a man approaching you with the obvious intent of doing you good,” advised Henry David Thoreau, “you should run for your life.”

The thing about Good Causes is that people can have a tendency to go overboard. What can result at times is Fanaticism, Puritanism. A combination of self-righteousness and cruelty to the “unrighteous.”

In the worst instances, theses tendencies can lead to conflicts, wars, cleansings, and purges.

“To do evil a human being must first of all believe that what he’s doing is good,” wrote the Soviet dissent Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. He was thrown in a Siberian prison camp by the Communist government for being insufficiently loyal to the regime. Of course, the Communists claimed to be creating a workers’ paradise even as they brought about Hell on Earth.

Every major atrocity in history has been perpetrated in the name of Good. “Of all tyrannies, a tyranny exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive,” wrote C.S. Lewis.

The delusion of one’s own goodness seems to be a psychological prerequisite for those who commit atrocities. The Dutch writer Joost Meerloo, who survived Nazi occupation, said this “delusional thinking inevitably creeps into every form of tyranny and despotism. . .This [delusion] starts with the leaders and is later taken over by the masses they oppress.”

When large numbers of people allow themselves to be whipped into a delusional frenzy of self-righteousness against some threat (real or imaginary), usually a group of “others,” we end up with the Salem Witch Trials, the Spanish Inquisition, the Chinese Cultural Revolution, or the Soviet Communism that oppressed Solzhenitsyn.

It cannot be emphasized enough that everyone caught up in these mass hysterias believed that what they were doing was morally correct, and necessary for the greater good of the society as a whole, even as they killed and abused on a historic scale. They were caught in the delusion Solzhenitsyn warned about: Evil masquerading as Good.

Oppression always masks itself as Empathy.

It has happened so many times it really shouldn’t be necessary to point out the obvious, but history repeats itself, and these manias are always presenting themselves in a new form that people cannot recognize, because it always comes wrapped in a disguise that has never been used before, one that appeals to the peculiar fears, biases, and sense of “virtue” of that particular time period. “Every age has its peculiar folly: some scheme, project, or fantasy into which it plunges,” wrote Charles Mackay, the author of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, in the year 1841.

So, while the fear of witches does not motivate a modern urbanite, other kinds of fears do. While religious sanctimony no longer drives many people, newer and trendier forms of sanctimony do. And these can be used to stir up fanatical rages.

If and when the historical pattern inevitably repeats itself, and a new Good Cause arises, how confident are you that you will recognize it?

What if another Good Cause comes along that whips the population into a righteous frenzy, divides the world into “us” and “them,” and gives the “good guys” a perfectly respectable reason to rush out and slay a new set of dragons? Would you recognize the signs?

Surely you would recognize hatred if it speaks in a loud voice and shows an angry face, and approaches from the direction of your ideological and political opponents. That’s easy. But what if it comes from your own side, appealing to your own sensibilities? What if it shows up in a trendy disguise, throwing around fashionable, gentle words like “Love, Children, Planet,” to conceal its fanatical impulses?

Frank - 'Love, Children, Planet' - Schaeffer

Anti-**** and anti-**** anti-**** conspiracy theory-spreading leading activists are bio terrorists. Period. They should be treated as such. Drone strikes on selected worst offender pod-casters anyone?

There's nothing left to say to the anti-***** bio-terrorists but this: May you get the ***** now or perish quickly so the rest of us and our children and grandchildren may live.

(MSNBC News Contributor, Frank Schaeffer, spreading ‘Love’)

This is empathy, weaponized. The desire to be a “good” person—as opposed to one of the others, the “bad” people—can always be twisted by fanatics into a weapon for doing horrible things.

What crusaders and dragon-slayers tend to forget, as they get caught up in their own crusade, is that “the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either, but” Solzhenitsyn said, “right through every human heart.”

Learning the Same Lesson, Again and Again

One of the reasons I like writing fiction is that literature is an art form that can be used to explore more deeply the motivations behind human behavior, into the interior lives of humans—their beliefs and emotions and delusions—and thereby let us see humanity more clearly.

In contrast, social media—which more and more seems like a technology built for inducing hysteria, hatred, and division—makes every problem appear as if it is a simple issue of identifying the bad guys and attacking them. Whenever there is a story on social media about wildlife poaching, I notice all the vitriolic, hate-filled comments that wish death and torment on the poachers. Kill them all! In my book, I explore that impulse, but also the counter-impulse, which is to recognize the poachers’ humanity and the dire circumstances that drive them to commit these terrible crimes. This creates tension, which is the source of drama.

In my book, one of Anna’s realizations during her journey is that the poaching problem is not just “out there” with the bad guys, but something in which she is unwittingly complicit, too. The destruction of the planet and its wildlife is something built into a way of life that she herself is part of. In some ways she’s even more to blame than the people who pull the trigger, because she occupies a higher place in the global economic hierarchy. She can hurt and kill the bad guys, but she cannot hide forever from herself. She must confront her truest self and defeat her own internal flaws and fears before confronting the external causes of the crisis. It’s a dramatic personal dilemma with no clear or easy answers.

See, the evil that lurks in every human heart, which Solzhenitsyn talked about, is something that each person must face. The hero or heroine of a good story must go through the arduous process of identifying and confronting evil in himself or herself, and then defeating it. The scholar Joseph Campbell called this timeless drama “The Hero’s Journey,” and his ideas form the basis for many of our most memorable novels, movies, and other stories (one example being Star Wars - see the Power of Myth below). There is no real drama or heroic journey in blaming a group of “others,” and scapegoating them for all of the world’s problems – as in, they are “bad,” and we are “good.” (This is why so many stories are boring. They set up good guys vs. bad guys without any real, internal conflict).

A lesson human beings apparently need to learn over and over again through art, literature, meditation, philosophy, and the disastrous real-world consequences of overzealousness, is to be careful about believing too strongly in your own “goodness,” and beware those who are only too willing to impose their goodness on everyone else. They are always more dangerous than they appear.

(More in Part 2 of this Essay)

What I’ve Been Reading

Here are some links related to the essay above, and some of the things I’ve been reading lately. I’m an eclectic reader, to say the least . . .

The Gulag Archipelago, by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn - The epic masterpiece about the author’s experience of oppression in the Soviet Union.

Dark Star Safari, by Paul Theroux — Theroux is one of my favorite writers. He grabs you in the first sentences with his unique voice, by being contrary and unexpected, like these first sentences of Dark Star Safari: “All news out of Africa is bad. It made me want to go there. . .” Classic travelogue of his journey from Cairo to Cape Town.

The Mosquito Coast, by Paul Theroux — A modern classic novel by Theroux depicting a brilliant, idealistic father who tries to escape the madness of modern civilization with his family, but takes things too far. Unforgettable setting in the remote coastal areas of Central America. It was made into a good but not great movie starring Harrison Ford in the 1980s.

The Power of Myth, by Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers — I consciously tried to structure my book on Joseph Campbell’s ideas of The Hero’s Journey. While the Power of Myth book is very good, I actually recommend the video miniseries as the best introduction to his work. Campbell sat down with Bill Moyers for a series of long conversations at George Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch. Lucas based the Star Wars story on the Hero’s Journey. Many aspects of those movies that fans love—the Force, for example—came straight from Campbell.

The Constant Gardener, by John Le Carre - An intelligent and powerful novel, made into a 2005 Hollywood film, about the secret machinations of a Big Pharma corporation (based on a real pharmaceutical corporation starting with the letter “P”) that killed numerous African children with shoddy, unethical drug trials in the midst of an epidemic, then tried to cover it all up.

Blogs / Substacks

I am partial to the essays of Charles Eisenstein and Paul Kingsnorth. I am also picking my way through Kingsnorth’s excellent book, Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist.